By Megan Slobodin

A year ago, my husband passed – unexpectedly, suddenly. I felt myself plunging deep into grief, fighting for air, and forcing myself to take active steps just to keep myself alive. Coming to grips with the loss of my partner and best friend was devastating enough. Realizing the magnitude of all the secondary losses that accompanied it sometimes felt insurmountable. I was unprepared for the loss of identity, for the lost sense of personal safety and security. I was unprepared for the loneliness. Suddenly I was having to confront everything I had taken for granted in my life. I began a diary to track what was happening. Excerpts from that diary and from my blog on solitudes are below.

0-3 months

And then descends the yawning chasm of his absence. And nothing now makes sense. There is no purpose. I am a dog with three legs. “There goes that poor dog,” people say. But I no longer care what people think. I put the news on to listen to the noise but I can’t make sense of the words. I am no longer interested in discovering places. My world is one place only, and consumes me completely: a previously little-known inner landscape of profound loss, unremitting grief, my body no longer under my control. Dizzy, disoriented, tearful, hands shaking, sleepless, listless, nauseated, aching heart, breaking heart: the physical symptoms of grief ripple their way through me, and I am astounded.

Teeming with saturated grief just under the surface of my skin, I feel delicate, like broken china freshly glued. If anyone says anything to me about him, the fluid wells up and I find myself speechless, and just nod. I walk about my errands scanning other people in case I know them, so I can look away and not have to engage. Self-imposed isolation.

My mind is 100% of the time on him, so there is really nothing left over for anyone else. They wonder why my conversation suddenly drifts off and I am unaccountably staring off into the middle distance. I am looking for him, replaying where I last saw him, turning over the leaves of my heart to unearth memories that might remind and console. I turn back distracted to them, and mumble an apology. Could others take this constant feeling that they are a stranger in a strange land, lost with no bearings, slowly understanding they will never see their lost person again, despite looking for years? I am an empty half. There is no joy. I am biding yawning time.

It is tiredly reliable now, in this new life, quite predictable actually, that I get by each night on only four hours of sleep. At 4:00 am I regularly come awake now, the quiet whirr from the fan filling the room, my dog shifting watchfully beside me. I look at the cracks of light around the dark-out blinds, gauging the hour. The phone under my pillow confirms the time. I lie, eyes half open and staring somewhere between the world of sleep and dreams, where I might yet find him, and the landscape of my approaching day, from which the imperatives of his lifeforce have unaccountably withdrawn. The day is my own; I just have to find a way through it.

3-6 months

Grief has no mercy. Each time it comes as raw as that first dreadful moment when you understood you were standing on the cliff’s edge and the wind was blowing hard and you didn’t know which way to fall. Each successive time grief comes, you are not standing any further back from the edge, you are still right upon its verge. And every single time it frightens you with its intensity.

Grief is foremost a weight, like a heavy wet wool blanket in shades of black and greys and brown, wrapped around and around. Suffocating. It weighs me down and makes me slow when I used to be quick as lightning. Grief is the air I take in and out of my lungs, trying to breathe when my breath comes out in gasps. Grief saturates my cells, coats my skin. It is the shaking in my hands, the stumbling in my feet. Grief is the tears unbidden and unwanted, slipping down my face even when I am not thinking of him, and grief is me not caring.

As little time as I have been along this bleak and uneven path of grief, my opportunities for relief have come only from being mindful of the moment. Looking far into the future is relentlessly like a knife through the gut, doubling me over. The middle distance causes only anxiety and worry. My view of today, of this morning, of this particular moment, keeps all the competing landscapes at bay. I will be kind to myself and feel into only what I’m doing in this moment. These mindful moments are the only ones that offer me peace. Bolstered by the tranquility of the moment, I quietly allow in thoughts of my husband, letting in a little at a time, and rush back to the breath when it threatens to overcome. Returning to the breath is the only thing that makes the process of grieving even tolerable, the living of this new life endurable. It is not a practice of self-kindness so much as a strategy for continuing survival, day by day.

I cannot gauge well what is happening to me. My best mentors in a culture that does not feel comfortable with grief and lacks the conversational architecture to sustain its weight, is to read books about grief.

Today was one of those “afresh” days, the early morning when I first awake and realize afresh that I will be living the rest of my life without ever seeing him again. I had been exempt from an afresh for a few days, been able to think about him in depth without tears, had even indulged in some reading that for once was not about grief. I thought I had turned a small corner. But each afresh brings with it a reminder that this is a journey without corners, that I will not be able to “turn a corner” from my grief and gain some distance with that old feeling that life is good and full of joy and meaning and purpose. Grief is like humidity, and just hangs in the air, but like our air that is full of smoke from neighbouring forest fires, it is hard to see through to any distance.

A phone call from a well-meaning friend yesterday, when I thought I might be strong enough to weather the insensitivities of the casual enquirer, helped place me into the path of my latest afresh. As she chattered on about how lovely and perfect her life is currently, she enquired without real expectation of response in the midst of so much of her talking “So, are you still reading all those books about grief? Not reading anything new and interesting?”

Some days I feel I have read every book about grief that is out there. At first I read to get my bearings, tossed upside down and gutted by his departure. Then it was to find resonance with others, commonality of experience that let me know I was not going crazy in this new world. And my understanding of grief has slowly grown, and I wonder at all the traumas people endure in their lives that they are unaware of, carrying around a sad, saggy weight that draws them down, turns light step to trudges through vast tracts of their lives.

And so I write. Perhaps by articulating my emotional storm, I can lessen the electrical charge of grief when it returns to cast me gasping up onto the shore. It will be seen in time. For now, writing every day is part of my mindfulness meditation on him, returning to the page when, shaking, I have ventured too deeply into the whole mess of it all.

I never knew that grief strips you down, sheds you of your confidence, strips away your happiness, casts off your personal power, steals your identity. Grief also takes over your physical body like an alien being, an earwig, makes you nauseous, makes your heart race and feel like breaking, puts you off-balance, makes you shaky, makes you doubt your capacity to survive, causes the world to move in and out of focus though you try hard to look clearly, makes tears flow for every reason and for no reason at all.

Looking over my shoulder, I can see that part of this journey has been coming to understand in the darkness that only I can come and rescue myself. I’m still learning that path. I’m relearning the strength he saw in me. It’s not that I had lost my strength, it’s that I had come to over-rely on our combined strength, and now I need to tease out the filament that is mine alone.

6 – 9 months

People who are grieving play through endless scenarios in their minds, like the universe of all possibilities. We’re emotional masochists. We plod through every possibility, torturing ourselves with all the “what if’s” of our imaginations. The only time I have ever found benefit to the “what if’s” is in realizing how relieved I am that I was the one to outlive him. I accompanied him to his end of days, and not the other way around. Outliving him and becoming the one having to acquaint myself with the depths of grief was my final sacrament in our married vows.

I am tired this morning, so very tired of this new life of mine where everything takes so much effort, where I am constantly pushing at my back to get through to the end of each day, just so I can perhaps sleep and then have another day like this one. Grief is for long-distance endurance now, this new life sentence. It both frightens me and makes me weary. I did nothing to earn this “rest of my life”, yet it is inexorably in my face every day. There is no escape from it, this I have come to know. I am sailing perilously close to the winds of self-pity today, and I miss him desperately.

Recently I look in the mirror with wonder at the way my face has changed in seven months, my skin and contours claiming the cellular imprint of his absence. A new visage I don’t claim as mine yet, since I am waiting in transition, but one day my skin will sit upon a face more settled by the seasons of this grief, and I will know it for mine.

The shock has finally worn off and the realization that he is gone forever from this life has settled in like hardening cement. I started off this grief journey resentful and self-pitying that we were supposed to spend the rest of our lives together and that we were robbed. Now I think I realize from the universe that we only ever were going to have lives that intersected, travelled together for a while, gave each other gifts like our children, then parted toward our own destinies, souls on separate paths. My continuing suffering seems to rely on the belief that he irrevocably was mine for the rest of my life, that he belonged to me, and that I have been cheated. Yet by turns my grief becomes gratitude that I got him for my companion for such a seminal part of our separate destinies that we shared for a while. I loved that time together, but I would just feel better about my future path if I could be assured that he is alright, loved and blessed somewhere, secure and happy with his own result. I just still miss him so, and have unfinished conversations I suppose I will have to have in my head to resolve.

First anniversary of his passing

The first anniversary of death is the most dreaded date in one’s first year of grief, and there are plenty of hard dates to get through before then: his birthday, our wedding anniversary, my birthday, all the first holidays, and every plodding day in between. But looming always in the distance are the earth’s inexorable revolutions returning to that now terrible date of the happening itself: the hard medical news, the final conversations and decisions, the insistent affirmations of love, the gratitude for each other, the waiting, the last breath, the sudden ineffable shock of it. The tectonic shifting in my existence, where all the rest of it falls away and becomes backdrop.

What I did not bargain for were all the notes and calls and texts and memories of him flooding in from friends and loved ones, touching base with those who love him, who care for me, who send their kindest most gentle remembrances to me as their remaining best link with him. I welcome them all, and am so grateful he is remembered, and I am cared for. But this flow of energy and emotion into my usual isolation knocks me off balance, not by reminding me of that date last year particularly, but by emphasizing what I’ve been feeling since then in steady allowable measures, but now withstand in a torrent: just how much I lost when he passed from this world.

The anniversary doesn’t pass without the stunning realization that I survived the passage of the first year where grief is marked in daily slogging increments, hourly chasms, and thousand-yard stares. Survival comes at a price. It is only in looking back from where I came that I can better see who I was and who I am now, and I note with awed certitude that I am simply not that person anymore. So grief must answer for the parts of who I thought myself to be, that may now be missing more than they are present, and for the new additions that have been layered in which I would never have thought would be part of my life journey. Sometimes I wonder if I recognize who I am, and I wonder if he would recognize me too.

Grief has taught me the fundamental lesson that I don’t control anything. It is an illusion that we can make plans and expect the universe to stick to them. In the end, I don’t think I have become something that I wasn’t. I think I have allowed more of who I really am to be revealed, to myself and others. Layers have been peeled away, my soul stripped bare in places, and I don’t have the inclination to cover it up. Soon it becomes my new skin.

My love for him is absolute. But grafted to our love is a personal grief that I know now will be a current running through the remainder of my existence, sometimes erupting in a bright charge here or there when something triggers, but always a thrum, a low vibration invisible to the human eye, yet heard in the human heart.

Copyright Megan Slobodin, 2020.

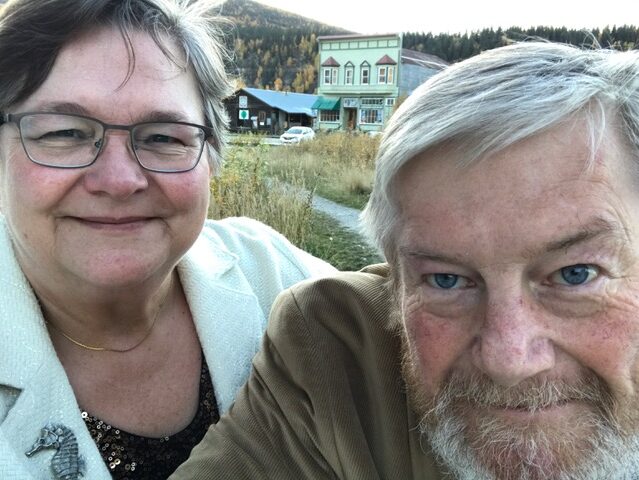

Note about the author:

In 2020, Megan donated her extensive collection of books on Grief and Loss to the Hospice Yukon lending library, in loving memory of her husband, Brent Slobodin.

In March 2020, Megan began a blog (Northerncoronagrief.com) to catalogue the various faces of solitude which come from living in the north, living in isolation under the coronavirus, and the ever-constant living with grief.